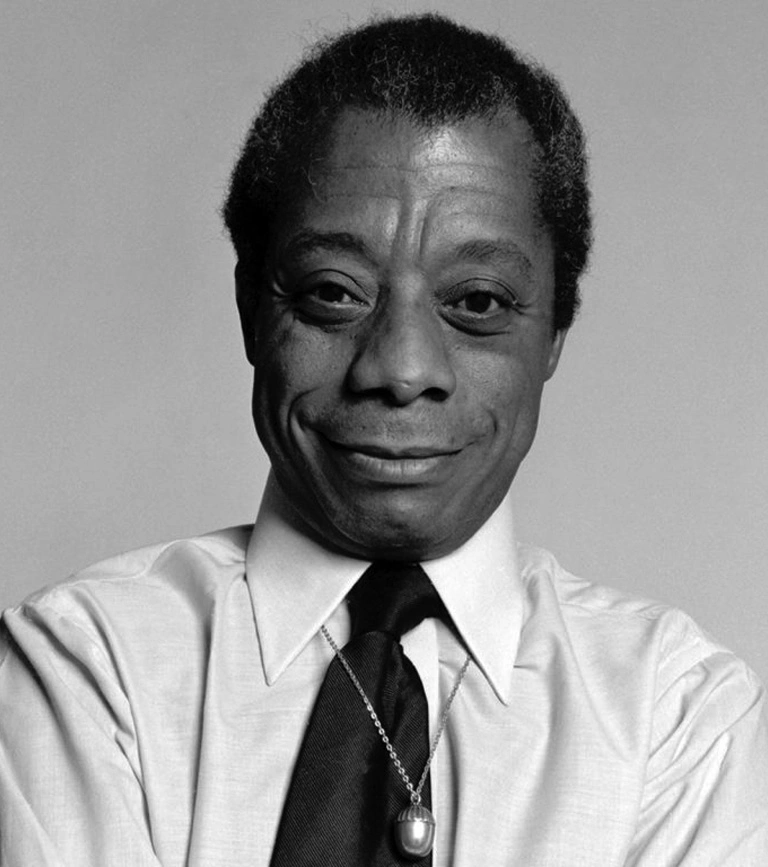

James Arthur Jones

August 2, 1924

December 1, 1987 (aged 63)

James Baldwin was born as James Arthur Jones to Emma Berdis Jones on August 2, 1924, at Harlem Hospital in New York City.

He was reared by his mother and stepfather David Baldwin, a Baptist preacher, originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, whom Baldwin referred to as his father and whom he described as extremely strict. He did not know his biological father.

Baldwin wrote comparatively little about events at school. At five years old, Baldwin began school at Public School 24 on 128th Street in Harlem.

The principal of the school was Gertrude E. Ayer, the first Black principal in the city, who recognized Baldwin’s precocity and encouraged him in his research and writing pursuits, as did some of his teachers, who recognized he had a brilliant mind.

By fifth grade, not yet a teenager, Baldwin had read some of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s works, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, beginning a lifelong interest in Dickens’ work.

Baldwin wrote a song that earned New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s praise in a letter that La Guardia sent to Baldwin. Baldwin also won a prize for a short story that was published in a church newspaper.

During his early teen years, Baldwin attended Frederick Douglass Junior High School, where he met his French teacher and mentor Countee Cullen, who achieved prominence as a poet of the Harlem Renaissance.

Baldwin went on to DeWitt Clinton High School, where he edited the school literary magazine Magpie and participated in the literary club, just as Cullen had done when he was a student there.

By high school graduation, he had a group of close friends from DeWitt Clinton—Richard Avedon, Emile Capouya, and Sol Stein—with whom he kept in touch and even collaborated on some of his works (e.g., Avedon and Stein).

The 1940s marked several turning points in Baldwin’s life. In 1942, he graduated from high school, and a year later he witnessed the Harlem Race Riot of 1943 and experienced the death of his father.

After this emotional loss, Baldwin felt more than ever that it was important to play father figure to his eight brothers and sisters. He could not even dream of college and, therefore, worked at menial jobs during the day and at night played guitar in Greenwich Village cafes, where he also wrote for long hours, trying to fulfill his dream of becoming a writer.

In 1944 Baldwin meets writer Richard Wright, who refers his first draft of Go Tell It On The Mountain to Harper and Brothers publishing house.

In 1948, at age twenty-four, Baldwin left the United States to live in Paris, France, as he could not tolerate the racial and sexual discrimination he experienced daily.

As Kendall Thomas, professor of law and critical race studies at Columbia University, explains, Baldwin left his country because of racism, and Harlem because of homophobia—two aspects of his identity that made him a frequent target of beatings by local youth and the police.

When asked about his departure, Baldwin explained in a The Paris Review interview from 1984, “My luck was running out. I was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed.” In Paris, Baldwin began to interact with other writers.

He reconnected with Richard Wright, and for the first time, he met Maya Angelou, with whom he maintained a close relationship until the end of his life.

Baldwin would spend the next forty years abroad, where he wrote and published most of his works. In his early years in Paris prior to Go Tell It on the Mountain’s publication, Baldwin wrote several notable works.

“The Negro in Paris“, published first in The Reporter, explored Baldwin’s perception of an incompatibility between Black Americans and Black Africans in Paris, as Black Americans had faced a “depthless alienation from oneself and one’s people” that was mostly unknown to Parisian Africans.

He also wrote “The Preservation of Innocence“, which traced the violence against homosexuals in American life to the protracted adolescence of America as a society.

In the magazine Commentary, he published “Too Little, Too Late”, an essay on Black American literature, and “The Death of the Prophet”, a short story that grew out of Baldwin’s earlier writings for Go Tell It on The Mountain.

In December 1949, Baldwin was arrested and jailed for receiving stolen goods after an American friend brought him bedsheets that the friend had taken from another Paris hotel. When the charges were dismissed several days later, to the laughter of the courtroom, Baldwin wrote of the experience in his essay “Equal in Paris”, also published in Commentary in 1950.

In the essay, he expressed his surprise and bewilderment at how he was no longer a “despised black man” but simply an American, no different from the white American friend who stole the sheet and with whom he had been arrested.

In these years in Paris, Baldwin also published two of his three scathing critiques of Richard Wright—”Everybody’s Protest Novel” in 1949 and “Many Thousands Gone” in 1951.

On December 1, 1987, Baldwin died from stomach cancer in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France.

Baldwin’s work fictionalizes fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures.