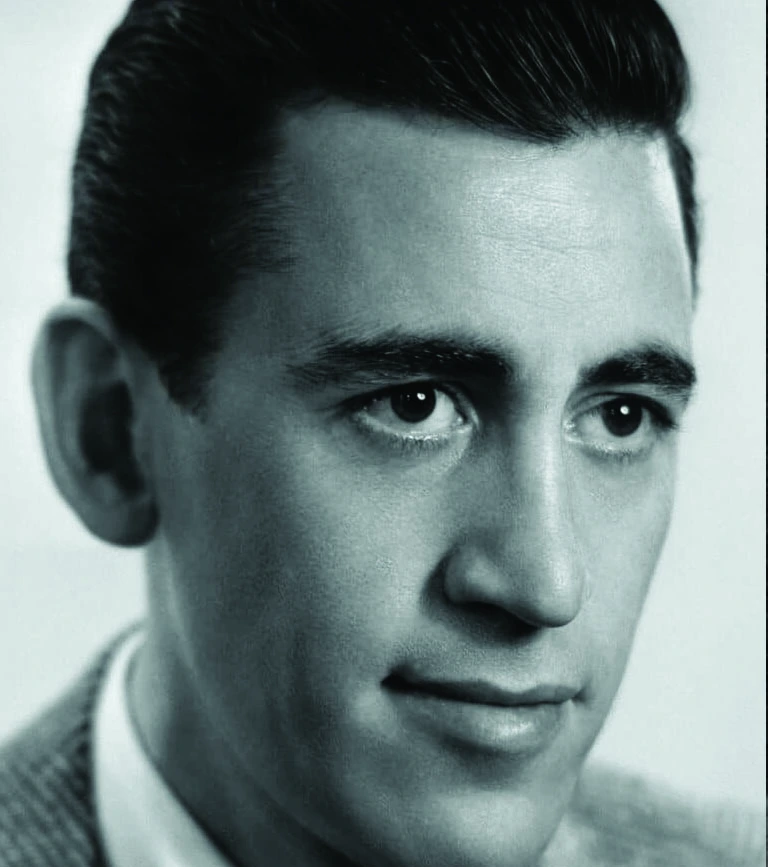

Jerome David Salinger

January 1, 1919

January 27, 2010 (aged 91)

D. Salinger, best known for his controversial novel The Catcher in the Rye (1951), is recognized by critics and readers alike as one of the most popular and influential authors of American fiction during the second half of the twentieth century.

Jerome David Salinger was born in New York City on January 1, 1919, and like the members of the fictional Glass family that appear in some of his works, was the product of mixed parentage—his father was Jewish and his mother was Scotch-Irish.

Salinger’s upbringing was not unlike that of Holden Caulfield of The Catcher in the Rye, the Glass children, and many of his other characters.

Unlike the Glass family with its brood of seven children, Salinger had only an elder sister. He grew up in fashionable areas of Manhattan and for a time attended public schools. Later, the young Salinger attended prep schools where he apparently found it difficult to adjust.

In 1934 his father enrolled him at Valley Forge Military Academy near Wayne, Pennsylvania, where he stayed for approximately two years, graduating in June of 1936.

Salinger maintained average grades and was an active, if at times distant, participant in a number of extracurricular activities. He began to write fiction, often by flashlight under his blankets after the hour when lights had to be turned out.

Salinger contributed work to the school’s literary magazine, served as literary editor of the yearbook during his senior year, participated in the chorus, and was active in drama club productions. He is also credited with composing the words to the school’s anthem.

In 1938 Salinger enrolled in Ursinus College at Collegeville, Pennsylvania. While at Ursinus he resumed his literary pursuits, contributing a humorous column to the school’s weekly newspaper. He left the school after only one semester.

Obviously an intelligent and sensitive man, Salinger apparently did not respond well to the structure and rigors of a college education. This attitude found its way into much of his writing, as there is a pattern throughout his work of impatience with formal learning and academic types.

Despite Salinger’s dislike of formal education, he attended Columbia University in 1939 and participated in a class on short story writing taught by Whit Burnett (1899–1973).

Burnett, a writer and important editor, made a lasting impression on the young author, and it was in the magazine Story, founded and edited by Burnett, that Salinger published his first story, “The Young Folks,” in the spring of 1940. Encouraged by the success of this effort, Salinger continued to write and after a year of rejection slips finally broke into the rank of well-paying magazines catering to popular reading tastes.

Salinger entered military service in 1942 and served until the end of World War II. He continued to write and publish while in the army, carrying a portable typewriter with him in the back of his jeep.

After returning to the United States, Salinger’s career as a writer of serious fiction took off. In 1946 the New Yorker published his story “Slight Rebellion Off Madison,” which was later rewritten to become a part of The Catcher in the Rye.

In 1951 Salinger’s masterpiece The Catcher in the Rye landed at bookstores. It is little wonder that The Catcher in the Rye quickly became a favorite among young people; it skillfully demonstrates the adolescent experience with its spirit of rebellion.

At various points in history, The Catcher in the Rye has been banned by public libraries, schools, and bookstores due to its presumed profanity and rejection of traditional American values. Despite its popular success, the critical response to The Catcher in the Rye was slow in getting underway.

It was not until Nine Stories, a collection of previously published short stories came out in 1953 that Salinger began to attract serious critical attention.

Salinger did not publish another book until 1961, when his much anticipated Franny and Zooey appeared. This work consists of two long short stories, previously published in the New Yorker. In 1963 Salinger published another Glass family story sequence, Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters; and Seymour: An Introduction, again from two previously published New Yorker pieces.

Both stories revolve around the life and tragic death of Seymour Glass, the eldest of the Glass children, as narrated by his brother Buddy Glass, who is frequently identified as Salinger’s alter-ego, or a representation of the author’s personality.

While Salinger’s fictional characters have been endlessly analyzed and discussed, the author himself has remained a mystery. He consistently avoided contact with the public, obstructing attempts by those wishing to pry into his personal life. In 1987 he successfully blocked the publication of an unauthorized biography by Ian Hamilton.

The trauma from the war resulted in a nervous breakdown after which Salinger was hospitalized. While under treatment, Salinger met his first wife Sylvia, probably a German Nazi. The two stayed in marriage for a short period of 8 months only. In 1955, Salinger married again, Claire Douglas, daughter, of a noted art critic. Maintaining the marriage for a little more than 10 years, the couple had two children. Six years after his divorce, a new relationship bloomed when he noticed the name of Joyce Maynard, whose story in New York Times Magazine impressed Salinger after which he started a series of intense correspondence with her.

Joyce soon moved in with Salinger and was lashed out after 10 months. In 1998 Joyce wrote about her experience with Salinger, describing him to be an obsessive lover. Maynard was not the end of Salinger’s love life.

He was romantically involved with actress Ellen Joyce for some time after which he married Colleen O’Neill, a young nurse who remained his wife until his death on January 27, 2010.